Clinical Interoperability: Everything You Need to Know

What Is Interoperability in Healthcare?

Healthcare interoperability (also known as clinical interoperability) is the ability to effectively and seamlessly communicate, securely store, and share electronic health data in a timely manner. This allows relevant parties to access full medical histories within the healthcare ecosystem. Ultimately, the goal is to positively impact health outcomes for patients.

Defining Interoperability in Healthcare

The HIMSS (Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society) describes healthcare interoperability as:

“... the ability of different information systems, devices, and applications (systems) to access, exchange, integrate, and cooperatively use data in a coordinated manner, within and across organizational, regional, and national boundaries to provide timely and seamless portability of information and optimize the health of individuals and populations globally.

Health data exchange architectures, application interfaces, and standards enable data to be accessed and shared appropriately and securely across the complete spectrum of care, within all applicable settings and with relevant stakeholders, including the individual.”

Four levels of interoperability need to be in place:

- Foundational: The ability to share data from one source to another, e.g., emails and PDFs.

- Structural: The ability for data to be opened and used on different systems, e.g., standardized data formats, syntaxes, and structures such as codes, identifiers, and simple text.

- Semantic: Using standardized vocabulary and terminology establishes a common foundation for data input. Examples include the Medical Dictionary for Medical Regulatory Activities (MeDRA)1 and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD 10) codes.2

- Organizational: Refers to regulatory and legal governance, oversight, policies, and other organizational considerations.

Why Is Interoperability Important in Healthcare?

Complete visibility of patients’ healthcare and medical records is critically important. This enables relevant parties—patients, care providers, labs, researchers, payers, researchers, and public health administrators-–to make informed decisions.

Unfortunately, different versions of patients’ records reside in multiple disparate systems, making it difficult to see all healthcare data. This results in data duplication, gaps, or inconsistencies when accessing different electronic healthcare record (EHR) systems, electronic medical record (EMR) systems, and other sources. This creates potential issues, including errors in diagnosis or treatment and delays to patient care while tests are repeated unnecessarily. Delays have a significant impact on patients who are forced to live with life-changing or life-threatening conditions.

Additional data is collected now: demographics, lifestyle choices, behavioral patterns (smoking, diets, etc.), and genetic predispositions. This additional data allows care providers and public health administrators to carry out detailed analyses of overall healthcare needs and health trends, to make decisions regarding every element of the system-–to improve therapies, drive new developments, amend or create policies, identify gaps in medical histories, and improve quality of care.

The healthcare sector, regulatory bodies, and governments recognize that it’s critically important that relevant stakeholders have secure, appropriate, and timely access to necessary data to make healthcare decisions-–hence the need for interoperability.

Surprisingly, true interoperability does not exist everywhere…yet.

Key Benefits of Interoperability

As healthcare is data-driven, interoperability can benefit almost every aspect of the ecosystem.

The core benefits are:

Improved Patient Care

Patients receive a higher quality of care when providers have access to patients’ complete electronic medical records. Access to full healthcare data in emergency situations is particularly critical, where life and death decisions need to be made instantly by care providers. For example, if an unconscious accident victim is admitted into the emergency assessment unit of a hospital and the emergency team does not have access to complete medical records through their EHR/EMR (and therefore is not aware of an allergy to certain medications), treatment could result in a serious adverse event or worse.

Patient Empowerment

Many countries are working to empower patients with easy and full access to their medical data, helping them to take control of their healthcare, e.g., to seek second opinions, learn more about their health, and make numerous other healthcare-related decisions. Interoperability is the key to achieving this.

In the US, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published a ruling to achieve this “by liberating patient data using CMS authority to regulate Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, Children's Health Insurance Program, and Qualified Health Plan issuers on the Federally-facilitated Exchanges.”3

Cost Savings, Efficiencies, and Reduced Burdens

The financial impact of a lack of interoperability within the US healthcare industry has been estimated at $30 billion, which would be avoidable if a truly interoperable ecosystem existed.4 Many costs are attributed to inefficiencies and duplication of tasks. Examples include: increases in the length of stays for patients caused by delays in information transfer; adverse events that were avoidable if interoperability existed; redundant testing carried out due to inaccessible information; manual entry of information by healthcare professionals; managing duplicated or inconsistent data; and additional provider costs associated with integrating electronic health records and other systems.

Support for Public Health Initiatives

Government initiatives to improve public health need insights across the healthcare spectrum. The gathering of anonymized data to drive improvements, research, and developments, and to monitor progress is complicated by the sheer number of sources and complexity of data.

Interoperability enables quick, efficient, streamlined, and accessible routes to monitor health trends, track diseases, identify research and development opportunities, and highlight risks.

Regulatory Compliance

Globally, regulatory bodies and governments have responded to the critical nature of healthcare interoperability by issuing regulatory requirements and guidance. Examples include: the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA), whose guidance regarding medical device interoperability spans from 2010 to the present day;5 the UK Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)’s new Data Strategy that includes “Harmonized standards and ontologies permitting interoperability”;6 and the US Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA), the “universal governance, policy, and technical floor for nationwide interoperability” of the Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy/Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ASTP/ONC).7

Benefits for Clinical Research and Development

The clinical research and development sector leverages anonymized public health data to assist in multiple areas of clinical studies, including identifying opportunities, risks, and patterns within therapeutic areas.

The lack of interoperability and integration has been a long-term challenge in this area. Leveraging TEFCA will have a significantly positive effect.

Medidata is working on several use cases that have been made possible by leveraging TEFCA in our clinical trial solutions, including Medidata Health Record Connect, the myMedidata patient portal/app, and Rave Companion.

Clinical research and healthcare use cases where TEFCA can make a difference include:

- Data entry automation (EHR-EDC): This technology eliminates manual data duplication of EHR data into the EDC system and enables scalable data access.

- Patient recruitment: Allowing research sites to query their patients, create cohorts, and aggregate and visualize local cohorts for pharmaceutical and medical device clinical studies.

- Patient registries: Connecting patients’ medical records to registries to qualify patients quantitatively.

- Real-world Evidence (RWE): Collecting, aggregating, and analyzing data from multiple sources in the healthcare ecosystem, including EHRs, labs, claims data, and more.

Challenges to Achieving Interoperability

As mentioned above, true interoperability does not exist—even after decades of industry and regulatory collaboration.

The healthcare ecosystem is driven by vast volumes of data from many disparate sources—patient examinations, diagnosis, tests, treatment plans and records, demographic information, prescriptions, doctors’ notes, sensors, wearable devices, and other data generated across the ecosystem. It’s highly complex and multi-layered.

Key challenges include the following:

Sheer Volume and Velocity of Data

Manual processes and legacy systems cannot keep up with the sheer volume of data generated by the healthcare system. An average patient’s EHR is approximately 80 Mb per year.8 In 2020 the World Economic Forum estimated that 2.3 zettabytes, that’s 2,300,000,000,000,000 megabytes of data, was produced within healthcare, and this increases every year.9 Additionally the velocity of data, the sheer speed at which it can be generated for analysis, is staggering, particularly with the increased adoption of more technologically advanced systems and AI-assisted platforms.

Security and Privacy

Patient data is subject to privacy and security regulations and the accessibility needs of authorized stakeholders within the healthcare ecosystem. Guidance, regulations, and resources are in place to secure these, e.g., the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).10

Financial and Resource Limitations

The costs of upgrading legacy systems and implementing interoperable technologies can be off-putting, particularly for hospitals and smaller healthcare organizations with limited budgets and resources. When considering the risks to patients, financial losses from operational inefficiencies, and the inability to make fully informed data-driven decisions, the need for interoperability from an ethical, health, safety, and economic perspective is unquestionable.

Disparate Systems

Advancements in technology have seen a plethora of disparate systems offering solutions to enhance healthcare processes, usually designed to improve efficiency and speed, reduce costs, improve experiences, etc. While any system that can achieve this is very welcome, the disparate nature of these systems has also led to interoperability and integration challenges, which in turn have caused delays, costs, and additional resource requirements.

One of the main challenges has been the lack of unified standards in the industry, which leads us to the following topic:

Standardization

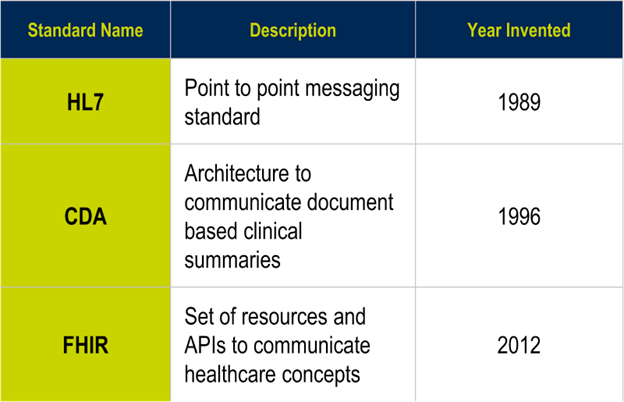

Due to interoperability challenges between EHRs and other systems, three major standards emerged that are still in use today:

- HL7 (Health Level Seven International) (1989):11 point-to-point messaging standard.

- HL7 CDA (Clinical Document Architecture) (1996): An architecture to communicate document-based clinical summaries.

- HL7 FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) (2012): A set of resources and APIs (application programming interface: a way of communicating with a particular computer program or internet service) to communicate healthcare concepts.12

As mentioned, the US healthcare sector loses billions, which is reflected in all countries' experiences. Efforts for standardization have fallen far short of their goals.

There are three core challenges to address: ambiguity and flexibility in data standards, challenges related to point-to-point connections or multiple networks, and the need for data-sharing agreements and trust frameworks.

The Future of Healthcare Interoperability

There are many important initiatives around the world to address the challenges of both national and cross-border interoperability.

The United States

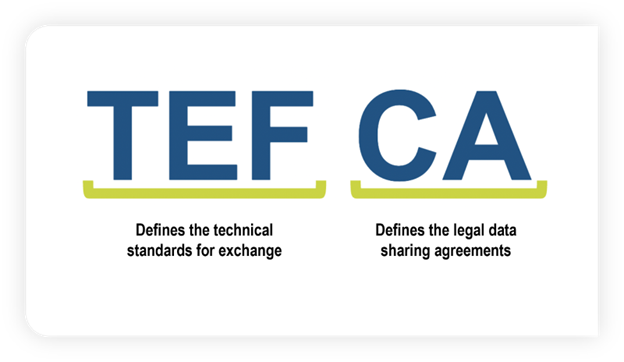

In 2016, the Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy/Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ASTP/ONC) called for a new framework, the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA), which was passed under the 21st Century Cures Act to interoperate and share data using gateways and networks.13 The Trusted Exchange Format (TEF) refers to the technical standards for exchange; the Common Agreement (CA) relates to data-sharing agreements that allow for open sharing of data within the network.

TEFCA was launched in 2021, and we’ve seen major developments since then with a growing network that shares health data across the US using data hubs called qualified health information networks (QHINs) and health information exchanges (HIEs).

This is a significant step towards true interoperability, empowering system and technology solution providers to participate in a unified data system and enabling the above benefits.

Europe

The European Parliament adopted the European Health Data Space (EHDS) that was put forward by the European Commission in 2022 and agreed upon in spring 2024. Hailed as a groundbreaking initiative, it aims to enable the EU to “fully benefit from the potential offered by a safe and secure exchange, use, and reuse of health data to benefit patients, researchers, innovators, and regulators.”14

Their goal is to “place citizens at the center of their healthcare, granting them full control over their data, with the goal of achieving better healthcare across the EU” and “to allow the use of health data for research and public health purposes, under strict conditions.”

The United Kingdom

The UK Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)’s new data strategy includes “Harmonized standards and ontologies permitting interoperability.”15 In October 2024, the UK government announced a plan to provide digital access to a single patient record with a full medical history, test results, and letters through a National Health Service (NHS) app, all part of their 10-year plans to overhaul the NHS. Current medical record access is available through local sources such as surgeries, clinics, and hospitals.

Internationally

Internationally and across borders, the International Patient Summary (IPS) is a “minimal and non-exhaustive set of basic clinical data of a patient, specialty-agnostic, condition-independent, but readily usable by all clinicians for the unscheduled (cross-border) patient care.” For example, if a person falls ill whilst traveling abroad in a country that uses IPS, the local care team can access a summary of the patient’s medical records, such as allergies or prescribed medications, but not their full medical history.

IPS is an HL7 FHIR-based standard that has been developed by the European Committee for Standardization/Technical Committee (CEN/TC 251),16 HL7, Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE),17 International and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) International,18 ONC, and the International Standards Organization (ISO), all led by the Joint Initiative Council (JIC).19

Launched in 2016,20 IPS was published by the ISO 215 Committee as ISO 27269:2021. The first IPS global deployment pilot played a part in the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) immunization block with the issuance of the international COVID-19 immunization certificate.

The IPS is currently under active development in many countries, including Canada, Latin America (Argentina and Brazil), England, Holland, Sweden, New Zealand, Malaysia, and Vietnam.21

The World Health Organization (WHO) supports the IPS, including supporting multiple languages for the ICD classifications and recommending international nonproprietary names for drugs.

In Summary

Patients, quality of care, the healthcare ecosystem, research and development, and government policies are all reliant on the full availability of healthcare data across the disparate systems used throughout. Interoperability is a critical requirement that impacts health outcomes, public health, and safety and has a major financial impact on everyone.

As healthcare practices and technology have evolved, the volume and velocity of data generated continue to increase exponentially year-on-year. The only way to realistically reach interoperability goals is to build a foundation for the industry by addressing the ambiguity and flexibility in data standards, to reach data-sharing agreements and trust frameworks, and to provide a technological mechanism that allows efficient data communication. The TEFCA initiative presents the foundation for these.

Healthcare technologies that leverage this new level of interoperability will be at the forefront of driving better healthcare outcomes. As Medidata has done, inevitably, technology solution providers will further innovate across the healthcare and clinical trial landscape in areas such as patient-centered care, personalized medicine, AI-driven decision support, data management, streamlined workflows, reduced burdens on resources, and enabling real-time data sharing between systems and stakeholders.

Financial and resource burdens will be significantly reduced, and, most importantly, patients’ lives will be improved and even saved.

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) states that the relationship of clinical trials with healthcare is “an essential part of the process of evidence-based practice and can help guide treatment decisions for both healthcare professionals and patients.”22

With the whole industry, regulators, and governments working towards truly global interoperability, Medidata is at the forefront of EHR integration with Medidata Health Record Connect—a solution that securely and compliantly acquires, transforms, and exchanges EHR data, allowing for an unprecedented level of collaboration and visibility into patients’ healthcare data.

References

-

-

-

- Medical Dictionary for Medical Regulatory Activities (MeDRA)

- International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD 10) codes

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CMS Interoperability and Patient Access Final Rule (CMS-9115-F), 2020 (updated in 2021)

- West Health, Interoperability: A call to action. HCI-DC 2014

- Food and Drugs Administration, Medical Device Interoperability

- Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, MHRA Data Strategy 2024-2027

- Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy/Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ASTP/ONC), Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement

- Gopal, Gayatri, Suter-Crazzolara, Clemens, Toldo, Luca and Eberhardt, Werner. "Digital transformation in healthcare – architectures of present and future information technologies" Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM), vol. 57, no. 3, 2019, pp. 328-335

- World Economic Forum (WEF), article for the WEF Annual Meeting, January 2024

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

- HL7 International

- Cambridge Dictionary, definition of API

- Food and Drugs Administration, 21st Century Cures Act

- European Health Data Space

- Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, MHRA Data Strategy 2024-2027

- CEN/TC 251

- IHE International

- SNOMED International

- Joint Initiative Council

- The International Patient Summary Story

- Beatriz de Faria Leao, Italo Macedo do Amaral Costa, Joice Machado, Monalisa de Assis Molla, Aline Rodrigues Zamarro, Fabiane Raquel Motter, Gabriel Gausmann Oliveira, Karla L de A Calvette Costa, Blanda Helena de Mello, Elivan Silva Souza, Gabriella Nunes Neves, Robson Willian de Melo Matos, Paula Xavier dos Santos, José Eduardo Bueno de Oliveira, Sabrina Dalbosco Gadenz, The Brazilian international patient summary initiative, Oxford Open Digital Health, Volume 2, 2024, oqae015, https://doi.org/10.1093/oodh/oqae015

- National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), Clinical Trials Guide

-

-

Contact Us